Seven Sermons to the Dead

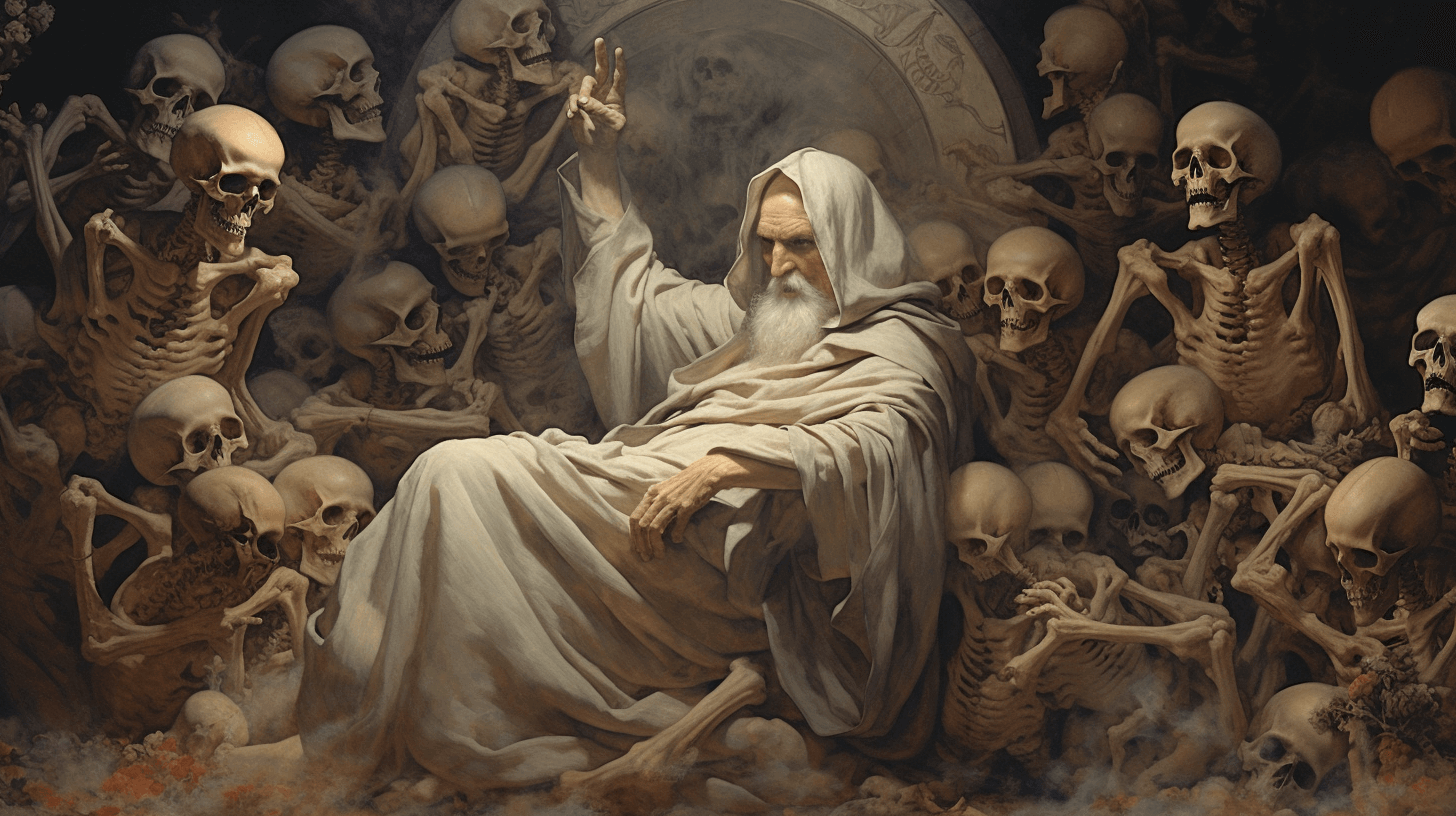

“Seven Sermons to the Dead” is a mystical text written by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung in 1916. The work was composed during a time of intense psychological transformation for Jung, which he called his “confrontation with the unconscious”. It is written in a prophetic, sermon-like style, and Jung signed it under the pseudonym “Basilides,” a Gnostic religious teacher from the 2nd century AD.

“Seven Sermons to the Dead,” which is part of his “Red Book” (“Liber Novus”). These “sermons” were imagined dialogues with the dead, written in the style of the Gnostic gospels. The Seven Sermons to the Dead are a part of this collection, where Jung explores several deep and complex themes related to individuality, divinity, the nature of the universe, and more.

These sermons serve as a symbolic exploration of the depths of the unconscious mind and are an essential part of the foundation of Jung’s later work in analytical psychology. “Seven Sermons to the Dead” is considered by many to be a significant text in the field of depth psychology and a unique contribution to Western esotericism.

The first sermon

The first sermon begins with a gathering of spirits in Jung’s house, disturbing him from his sleep. These spirits were lost in confusion after death, seeking answers.

In response, Jung delivers his first sermon, speaking about the Pleroma and the principle of the opposites.

The Pleroma: This term is borrowed from Gnosticism and essentially means “fullness” or “wholeness”. In Jung’s sermon, Pleroma is described as a state of complete emptiness and fullness. It is everything and nothing at the same time, a void that is also the origin of all existence. Jung argues that we come from the Pleroma and return to it after death. It’s a state where opposites cease to exist because they cancel each other out.

Principle of the Opposites: Jung emphasizes that the world as we know it exists because of differentiation from the Pleroma, and that differentiation is characterized by the opposites. Everything we perceive is based on the contrast of opposites. For instance, we can only perceive light because we know what darkness is.

Jung also suggests that human desire for unity or the ‘God’ within us is what draws us back to the Pleroma. However, he warns that the undifferentiated state is not preferable while we are alive because it is equivalent to death. The goal, instead, is to acknowledge and balance the opposites within us without being consumed by any one side.

These are complex metaphysical and psychological concepts, and the first sermon serves as a foundational explanation that helps inform the ideas presented in the rest of the sermons. Understanding it may require deep reflection and multiple readings.

The second sermon

In the second sermon of the “Seven Sermons to the Dead,” Carl Jung delves deeper into the principles introduced in the first sermon. He discusses the concept of Abraxas, a Gnostic god, in an attempt to provide an image for the unified divine principle that holds both the opposites.

Abraxas, in Jung’s sermon, is presented as a higher value or god than the Christian God and devil. Abraxas is the entity that combines all opposites into one being. He embodies both existence and non-existence, good and evil, light and dark, the perceptible and the imperceptible. Abraxas is not to be worshipped, but understood as the representation of the unbearable paradox for the human mind – the union of all opposites.

Jung then delves into the concept of God’s “emanation,” a term used in Gnostic literature to describe the process through which the divine principle unfolds into the manifest universe. He portrays the divine as a process of becoming rather than a fixed entity.

Jung also suggests that the world of appearances, which we take as reality, is just an illusory creation. The true reality is incomprehensible and can only be vaguely intuited.

He talks about the power of love and its association with death. Love, in this sermon, is not an emotion but a state of fusion that leads back to the Pleroma, the state of undifferentiated unity. But returning to the Pleroma implies the dissolution of the individual, a metaphorical death.

Towards the end of the sermon, he discusses the idea that every individual carries a piece of the divine and is an expression of the divine creative power.

The third sermon

In the third sermon of the “Seven Sermons to the Dead,” Carl Jung delves into the nature of the human soul.

Jung begins this sermon by suggesting that our souls are part of the undifferentiated, pleromatic reality, but they’re differentiated from it due to human perception. He presents the soul as a microcosm reflecting the larger macrocosm. Our souls are like a mirror of the wider universe. Therefore, the soul holds within itself the duality and conflict of existence that characterizes the larger world, such as good and evil, joy and pain, etc.

He further describes that there are multiple levels to the soul, which can be perceived in various ways, depending on our psychic state. The soul, according to Jung, appears in dreams, deep reflection, and other situations where the subconscious comes to the surface. He suggests that the nature of the soul is essentially unknowable because it is a reflection of the incomprehensible pleroma.

Moreover, he describes the soul as having a dual-gender nature. This refers to the fact that everyone, regardless of their biological gender, carries aspects of both masculinity and femininity in their soul, which is a theme that later becomes very important in Jung’s theories of the anima (the inner feminine side of a man) and animus (the inner masculine side of a woman).

Finally, he mentions that the gods (which should be understood as symbolic representations of the various forces that operate in the human psyche, according to Jung) reside in the soul. He insists that they have to be given their due – respected, understood, and integrated – to live a full life.

The fourth sermon

In the fourth sermon of the “Seven Sermons to the Dead,” Carl Jung continues his metaphysical and psychological exploration, turning his attention to the concept of “the devil” or evil and the role it plays in human life.

The sermon begins with the statement that the devil is the opposite of God. However, both are necessary for the existence of the cosmos. This aligns with the theme Jung has been developing in previous sermons, that the world we perceive is based on opposites and differentiation from the pleroma.

Jung then delves into the understanding of ‘evil’. He mentions that just as there can be no affirmation of pleasure without the existence of pain, so too we cannot comprehend ‘good’ without the presence of ‘evil’.

Jung portrays God as a representation of the highest good, while the devil represents the utmost evil. However, he emphasizes that they are not independent entities, rather they are two poles on a spectrum of human experience and understanding. The idea here is that the opposition of good and evil is a human construction, necessary for our perception and understanding of the world.

But the sermon goes further to say that both God and the devil are illusions emanating from the pleroma, the realm of pre-differentiated unity. They are both outcomes of our human need to differentiate and categorize, which results from our departure from the undifferentiated state of the pleroma.

The fifth sermon

In the fifth sermon of “Seven Sermons to the Dead,” Carl Jung shifts his focus from the opposites of good and evil to the human relationship with pleasure and desire. He delves into the concept of eros and logos, two fundamental forces in human life.

Jung begins this sermon by identifying two principles. The first is the principle of eros, associated with love, desire, and the joining together of separate entities. The second is the principle of logos, often associated with reason, order, and differentiation.

Jung suggests that these two principles are not simply about love and reason as we commonly understand them. Instead, he describes eros as the principle of connection and relationship, bringing things together and creating life. On the other hand, logos is the principle that enables us to differentiate and categorize the world, creating order and understanding.

He then describes how these two principles interplay in human life. When we live according to the principle of eros, we connect with others and the world, and life is filled with desire and pleasure. When we live according to the principle of logos, we see clearly and understand, but we may also become detached, as understanding often requires a degree of separation.

However, Jung also cautions against unbalanced attachment to either principle. Excessive adherence to eros can lead to a loss of personal identity, as the self merges with the other. On the other hand, a life dominated by logos can be detached and devoid of connection and relationship.

The sixth sermon

The sixth sermon in Carl Jung’s “Seven Sermons to the Dead” explores the nature of time, space, and being. As in the previous sermons, Jung continues to examine the fundamental principles that structure human experience, focusing here on our perception of existence.

Jung begins this sermon by stating that time and space are conceptions which belong to the world of differentiation and hence do not exist in the Pleroma, the realm of pre-differentiated unity that he introduced in the first sermon.

He goes on to describe time and space as ‘incalculable’ entities. They are essentially relative, dependent on the observer’s perspective. Without the human consciousness to perceive and measure them, they do not exist.

Then, Jung discusses the notion of being, saying that everything that we perceive in time and space is temporary, and only seems to ‘be’ for a moment. Because everything in the world of appearances (phenomena) is always changing, it has no permanent being. In the Pleroma, there is no change, and therefore, no time, space, or being.

However, Jung points out that our human consciousness is rooted in the world of appearances, and we are oriented towards understanding through the concepts of time, space, and being. We are not capable of perceiving the Pleroma directly.

The seventh and final sermon

In the seventh and final sermon of the “Seven Sermons to the Dead,” Carl Jung elaborates on the nature of the self and individuation. He focuses on the conflict between the individual’s personal sense of self and the broader collective identity.

He begins by stating that while the world exists in plurality, humans contain the world within themselves, thereby existing as a reflection of the world. This idea resonates with the concept that humans are microcosms of the macrocosm.

Jung suggests that the aim of individual life is to become an individual and, to do so, one must differentiate oneself from others. This is a reference to the process of individuation, which is a central concept in Jung’s analytical psychology. Individuation involves a person’s becoming aware of their individual nature, as distinct from the collective nature of their community or society.

However, Jung also stresses the importance of acknowledging and integrating the collective components of the psyche. He warns against inflated self-importance and ego-centrism, which can occur if the process of individuation is not balanced with an awareness of one’s relationship with the collective.

The seventh sermon suggests that the experience of life and selfhood is characterized by a tension between the collective and the individual, between the drive to conform to the expectations of society and the desire to assert one’s individuality.

Conclusion

The “Seven Sermons to the Dead” by Carl Jung present a profound exploration of human psychology and metaphysics, deeply influenced by Gnosticism and other spiritual traditions.

Through these sermons, Jung introduces several key concepts:

- The Pleroma: A state of undifferentiated unity, where all opposites are dissolved. It’s the origin and the end of all things.

- The Principle of Opposites: All things in the perceivable world exist because of differentiation from the Pleroma, and differentiation is primarily characterized by opposites.

- Abraxas: A Gnostic god embodying the totality of good and evil, representing the unified divine principle that holds both opposites.

- The Nature of the Soul: Our souls are part of the undifferentiated reality, but are separated from it due to our perception. The soul reflects the larger universe and holds within itself the conflict and duality of existence.

- Eros and Logos: Two fundamental forces in human life. Eros is the principle of connection and relationship, and logos is the principle that differentiates and categorizes the world.

- Time, Space, and Being: These are relative concepts that belong to the world of differentiation and do not exist in the Pleroma. Everything we perceive in time and space is temporary and has no permanent being.

- Individuation: The process of becoming an individual requires differentiating oneself from others while also acknowledging and integrating the collective components of the psyche.

In conclusion, the Seven Sermons to the Dead is an examination of the nature of existence from a Jungian perspective, exploring the tension between opposites, the relationship between the individual and the collective, and the paradoxical unity of all things in the Pleroma. Jung uses this work to delve into the deep layers of the human psyche and our understanding of reality. Each sermon is open to interpretation and can offer different insights depending on the reader’s perspective and understanding.